A few days ago I mentioned a comment used by Mark Twain, more than once I’m told, to convey a broad principle that perhaps the French are a people that cannot be trusted. My own study of history, including French provincial history, tells me maybe that condemnation is perhaps a bit too broad. How the bard came by the comedy lines he delivered in the 1880s no one knows, but I opened with his general low opinion of the French in several categories recently, with It is French, taken from one of his stand-up routines.

In one of those talks he mentioned a deplorable cultural behavior trait, describing it this way:

“It is illegal!” (pause)

“It is unfair!” (pause), Holding up a finger into the sky.

“It is dishonest!” (pause), jabbing fist into hand.

“It is unconstitutional!” (pause) spoken through clenched teeth.

Then holding a finger up, he bellowed:

“It is un-American!”, almost shouting.

Then after a longer pause, more hushed:

“It is French”

Years before I heard this piece on a Hal Holbrook LP, I had already been set up by a military officer now in the history books. His name was Richard McMahon, and he was a US Army colonel who played a pivotal role as the Army officer tasked to insure the money the United States was sending the RVN (Republic of Vietnam) to carry on the war with North Vietnam after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973 was being spent for what it was intended. He was the Army Attache. And he’s in the history books.

Col McMahon had been senior officer at Wakkanai, on Hokkaido, America’s main observation post of the USSR, and was transferred to Camp Zama near Tokyo, when HQ-USArmy-Japan was elevated to a major command, overseeing most of the Army’s Asian activities. He became its G2 (Intelligence) at about the same time I arrived at Camp Zama in the Spring of 1973. His chief aide, MAJ Guy, lived next door to me in the Zama housing area, Sagamihara, and we all became close social friends.

(MajGuy is mentioned in my pieces about Manos, a Tokyo “restaurant”, described here, which are stories in their own right.)

Col McMahon’s hobby was writing novels and travelogues, and Guy reported that he kept his secretary in a constant state of shock from the topics and language he used. It was the Paris Peace Accords that caused our post to be elevated to a major command. With adventures at Manos, and mountain trekking in the Japan Alps, describe here, still I knew nothing of his plans to go to Vietnam, and to spend the last year of his career in Saigon to monitor the draw down of the US involvement there.

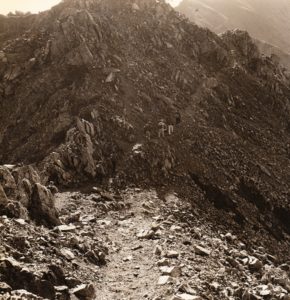

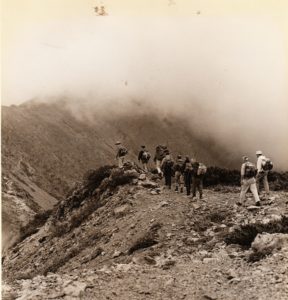

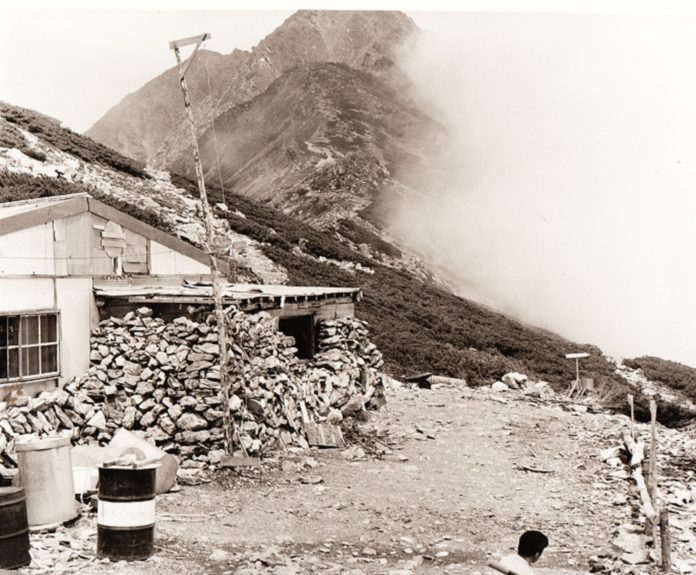

But in the Fall of ’72 he had organized a backpacking trip to the Japan Alps, and wanted to get the maximum publicity for it, since the Japan Alps had been closed to foreigners (gaijin) by General Tojo in the 1920s and no foreigner had ever been there since. There were five peaks there, and he wanted to climb three of them, Aino Dake, Kita Dake, and Nishi Notorii Dake. (I just listed them to prove that I could still remember their names). He and I would climb the remaining two in ’74, after taking a 4-day leave just to come and finish the scorecard. But that’s another story.

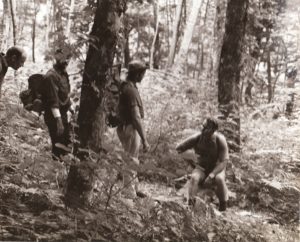

But in ’72 Col McMahon was able to put together a team of 10, and it was my first introduction to real backpacking. I’d hiked and camped all over the mountains of my mountain home…

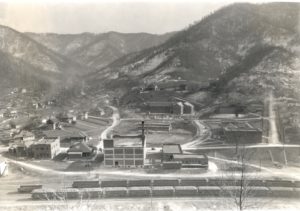

My Old Kentucky Home

My Old Kentucky Home

…but in my Kentucky mountains, I carried an old Army surplus rucksack and a sleeping bag…and a secret pack of cigarettes. This was high class backpacking in Japan. And being the first foreigners in those mountains in over 50 years, COL McMahon wanted to make a big splash so he had a Stars and Stripes photographer assigned. A great kid, and great photographer, what follows are some of his (award-winning) gallery, at least a few:

I have several more, the lower left showing Col McMahon, his deputy and my friend, Maj Guy and me with the moustache.

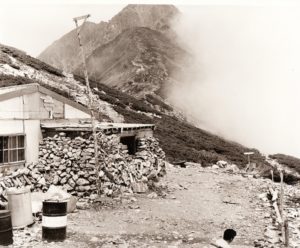

We stayed in huts each night, which consist of wooden bunks raised off the dirt floor, and wooden tables where we sat.

You may not remember the M.A.S.H. television series from a few years later, taken from the film that was released while I was in Japan. But our little troop had its own Father Mulcahy who was more like the television padre than than the film.

We were all sitting around two wooden tables, squatted cross-legged on cushions on the dirt floor. The lodge was out of Kirin so only had Sapporo Beer (one of the world’s finest to my tastes) plus sake, supported by rice, noodles and mizo shiru. I have no recall as to what the topic of conversation was, something about the French Revolution, I think, and how Bonaparte, a Corsican soldier, was brought in by the French intellectuals to tamp down the out-of-control way the French Revolution was turning. I was the junior officer, all were majors and light colonels, only myself and the padre, Mulcahy I’ll call him, were the only captains and I think Col McMahon decided to use that conversation as a teachable moment, having served in Military Intelligence in Paris before the Vietnam War broke out.

He simply stated that the French intellectuals did exactly what you’d expect intellectuals to do, bollix things up, and seeing this, a military genius declared himself king then decided to make a run at the whole of Europe.

And Col McMahon sort of threw his hands up and said, “It’s what the French do.” And he finished off his discourse by saying, “In the words of General Patton, you can’t trust anyone (the French) “who fight with their feet and fornicate with their face” (only he used the Brooklyn slang for ‘fornicate’.)

I was sitting next to Fr Mulcahy, and he broke into paroxysms of laughter. So we all joined in.

End of lesson

LOVE THIS Vassar!

Why, how nice!, Chris. I admire your observations, as well