In my freshman year in high school, 1960, I participated in the Kentucky high school regionals of what was called The State Speech Festival. Organized like Spelling Bee competitions, the best of the best at the regionals would be selected and sent onto state finals a couple of weeks later. I can’t recall all the categories, but ever since I was in first grade, we would gather in the high school gym and watch our best performers, juniors and seniors, do their presentations; dramatic readings. poetry, etc.

Being part of the East Kentucky region, this was also where students were supposed to show state leaders that we knew the difference between “fire” and “far” and could say it out loud. Without pausing first.

Being a freshman, this was just a preparatory trip for me, and I was entered in “Extemporaneous Speaking” where students would draw from a hat a theme, be given 20 minutes to think on it and then give a three-minute talk. I reached into the book and pulled out “Federal Aid to Education, A good idea?”

What?

Hell, I didn’t even know there was federal aid to education (which at the time there wasn’t) or that people were even fer it, or agin it. I paced and muttered for 20 minutes, then, when called, muttered my way through my presentation. At the end, I sat down, and received a “Satisfactory” for my efforts, which was the lowest rating a student could get, sort of like a B in high school English today, just for showing up. My student advisor simply told me I needed to start keeping up with current events, advice which I have assiduously adhered ever since.

When I got home my dad asked me how it went and what did I talk about. I told him “Federal Aid to Education

only I didn’t know anything about it,

Well, he sure did.

Dad was an engineer in the coal mines, but other than the set of encyclopedias on the book shelf, I don’t know if he ever read any book, as there were none in the house, other than mom’s half dozen Bibles on every lamp stand in every room. I assumed everything Dad knew was from reading the newspaper, or things he heard down at the VFW. (He would have been pushing 40 by then.)

But he stood up and launched into a veritable sermon on Federal Aid to Education, and how awful it would be…if it ever came to pass. His primary argument was (and we still hear today about everything government is involved in) that the money the feds gave schools would be “strings” on everything schools taught, negating the power of local citizens to decide just what schools should and could not teach their children.

Enter Earl Hodge

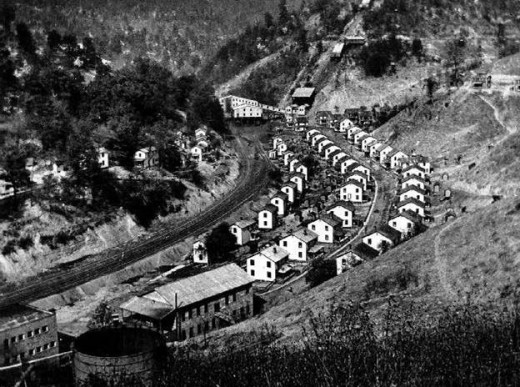

I may have mentioned Earl from time to time. He was a first shift mine foreman, and therefore had great seniority, so lived in a company house in the upper part of town, nearest the Big Store (the company store), the hospital, the mine offices, post office and the K-12 high school. That meant that children of ranking employees only had to walk 2-3 blocks to school, while the rest from a quarter-mile to a mile. (There was no school bus.)

Despite his rank, Earl was the foul-mouthedest man who ever lived.

When I think of Earl’s colorful language I think of Matisse’s blue period, bold colors in stark relief to an otherwise dreary conversation. Both his favorite verb and adjective were “goddamn”, and he could weave those into the simplest statements; about the sky, the grass, of Sybil’s (his wife) apple pie, which was delicious, by the way. He couldn’t make a simple declarative sentence of eight words without adding another three or four just for flourish.

In fact, he was so notorious that the women of the town showed up one day at the Mine Office demanding that the Company change its shift hours so that the first shift didn’t get off at the same time the children let out of school (around 3:30). It seemed many of the men would stop off at the Big Store, and sit and chaw out front, and if Earl showed up, a circle would form. It wasn’t long before boys from the school would make a beeline line to the Big Store to pick up new terms for their vocabulary from Earl Hodge. I know. I too had gone there once or twice and can still remember the stare from the dinner table, especially my older sister, when I blurted out one word I picked up from Earl, not even knowing what it meant. Sis gasped, Dad stood straight up and Mom ordered us both into their bedroom, when Dad informed me that word had something to do with a woman’s anatomy, and that it was the foulest, filthiest, ugliest word known to man.

The first shift soon began getting off work at 4:30.

So Earl was a legend.

And Earl’s son was also my best friend. Gary Wayne, only spoken as one word. I was two months older than Garywayne, and he lived the next street over, not even a 3-wood and an 8-iron’s walk. Since I never attended a birthday part in my life in that town I assumed no one could afford one. So Garywayne would come to my house on my birthday where Mom would fix sauerkraut and weenies, and I would go to his house for his mother Sybil’s famous pork chops. We did that for at least five years, all the way into high school when we discovered girls and the tradition ended.

It was at those sit down dinners around Earl Hodge’s kitchen table that I was able t learn lessons that would come back to me time and again over the coming years, just as I learned from the fist of Mick Hensley, in the same town.

Mom would always give me a little lecture about closing my ears to Earl. She was always “trepidaticous” about me going over there. But the Hodge kitchen table was arranged differently than ours. There were no other children, his oldest brother already married. Earl sat at the head of the table, Garywayne always to his left and me to his right. In the five years I went there to celebrate Garywayne’s birthday, I never once saw Sybil sit down. I’ve seen waiters in white servers jackets on the veranda of the Repulse Bay Hotel less attentive; always spooning our mashed potatoes or gravy, or a slice of her famous apple pie, or just standing by over Earl’s shoulder.

And Earl would be constantly grilling Garywayne about what he learned in school that day, each question carrying at least three expletives. It was a back and forth, and Earl seemed genuinely interested.

But on three occasions, when Garywayne answered, Earl shot out with the back of his left hand and popped Garywayne on the mouth, once causing it to bleed. Garywayne never cried, only lowered his head and said “Sorry, Dad.”

What was Garywayne’s sin? I’ll let Earl explain for I heard it here, “Ain’t no g-d son of mine going to work in that #*@&* coal mine. You’re going to get a g-d #*@&* education and get a job teaching g-d school or least a #*@&*’ing job in a car factory in Indianapolis.”

Then here’s the kicker, “The next g-d time you say that word, ‘ain’t’ in this house, I’ll really hurt you.”

It was in that vein, the same year I attended the Speech Festival, my mother and father had attended a PTA meeting at the school. As they came up on the porch my mother was reading the riot act to Dad. She was storming as they came in the door, “That old heathen!”, only Dad, instead of that shrinking violet look most husbands get when they’re being chewed out (in front of the kids), Dad had a sheepish grin.

As Mom stomped off the bedroom, Dad told Sis and me that Earl Hodge had stormed the meeting that night, still in his work clothes. Ranting down the aisle of the auditorium, yelling at the principal and board members on the stage, he wanted to know “why in the goddamn hell can’t you teach my boy not to say ‘ain’t’!” Then Earl said what I’d personally heard him say three times before, only dad never knew, “Ain’t no g-d son of mine going to work in that #*@&* coal mine. You’re going to give that kid a g-d #*@&* education, or else.”

Dad said Mom started praying under her breath, a couple of church women might have fainted, and some men stood up to bar Earl’s way to the stage. But as they were leading Earl out, a couple of other parents, both miners, stood up to say “Earl does has a point, you know.”

The rest of that meeting was about what the families expected of the school as regards their childrens’ future, and believe it or not, out of a little bit of fear, but also as a simple reminder of who was in charge at that school. Garywayne did finally drop “ain’t” from his vocabulary and eventually became a school teacher in Florida.

That was 1960, before John Kennedy was elected president. I graduated from high school in 1964, and from college in 1968. By that time, although every school district in America would g-d me for saying this, the federal government had completely taken over public education, all with dollars, and the proof, as Sybil Hodge would say, “is in the pudding.”

2 thoughts on “Famous Common People I Have Known, Earl Hodge and Federal Aid to Education”