And important lessons taught about “How Things Work”.

Luther Brock is that little fat kid on the second row, third from the right, with the star-struck, clueless look on his face.

This was our First Grade picture, 1952, and Luther and I were in the same classroom our first six years of school, roughly ages 7-thru-12. We were part of the first generation of Baby Boomers kids (born in 1946 to 1964) to enter American schools, and there were so many of us, over 50, they had to have two First Grade classrooms. That classroom stress would continue in that single building, which was originally designed in the 1920s for all grades, 1-thru-12, until the school had to be consolidated with another coal town, transforming into a large elementary school around 1961.

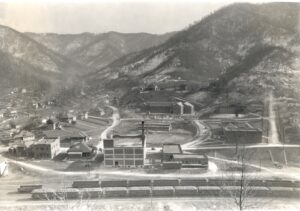

It was a company-owned coal town and believe it or not, all three of the houses I was raised in are visible in this 1930s photo, when my dad went to school there.

If ever a kid didn’t want to be in school, it was Luther Brock. First, as I pointed out, he was fat. Secondly, he was shy like you’ve never seen. Thirdly, Luther didn’t have any neighborhood pals to hang around with after school or on weekends, so didn’t have any buddies in school, all because he lived a quarter-mile out of town, down the creek, just across the town-line, underneath the bridge that crossed the creek just in front all those coal cars. This was because his dad, Roscoe, being the company’s prime mechanic for the coal cars that drove deep inside the mountain, a critical job, was given permission to live in the little village underneath that bridge, called “Frog Level”. Actually it was more of a slum than a village, with the backs of the small wood frame houses perched on stilts, hovering over the swift creek beneath them. That was because they had no indoor plumbing and they pooped straight down into the creek.

The very first house on that off-road was Roscoe Brock’s, as he’d asked special permission so he could run a part-time garage, where he fixed other miner’s cars. It was a good deal, having 150 coal miners as steady customers, since almost none of them ever owned a new car. My dad took both his ’49 and ’53 Nash down for routine work in the years Luther and I were in school together, and I went down with him a couple of times on Saturdays. Luther would be there with his head under the hood, standing on an overturned fruit crate.

Even at 8 he knew cars and how they worked. And I suspect he also knew what he wanted to do with his life, only it just didn’t include school.

In school Luther was a duck out of water. To say he was shy would be an understatement. He dreaded being called on by teacher, whether to identify a word as being a noun or a verb, or worse, being summoned to the blackboard. I remember watching Luther struggle with his 7’s, 8’s and 9’s multiplication tables…because teacher had made him stand at the blackboard until he could do a set, if only that one time. (He was never bullied, however for one, because we had high school football players who wouIdn’t permit it Yeah, imagine that). In class I never looked over at him that he wasn’t daydreaming out the window, probably wishing he was anywhere else, or thinking how stupid all this school-stuff was.

I never once saw him glance at, much less talk, to a girl.

Luther and I parted company when our school split up in the 9th grade, me going to a high school in the coal town up the creek, him going to the consolidated high school in the saloon-pool hall-and-grocery town two miles down the creek, just past Frog Level. It was a big city of over 5000. Then I went onto college, but I hitch-hiked back enough to know that the Brock car service was still in business. He was still a fatty, but boy did he know the internal combustion engine. By college he was working on modern 60s Chevy’s, Ford’s, and Pontiacs, and no more Kaiser-Frasers, or IH trucks, stuff I didn’t know a thing about. He was very proud.

So I’m quite certain Luther learned his math…only a need-to-know-basis…for by the time I left the mountains for good, joining the Army in 1971, Luther was running the garage.

Then, in the late 1990’s I drove back home for the last time, from Cincinnati down to that same school, which had been turned into a bed-and-breakfast, for a football reunion of the great state championships our high school had produced in the 50s and 60s. I got there a couple of hours early just to drive by some of the old haunts, Frog Level included, and there, by God, was that same old Brock’s Garage, only it had a new facade. I stopped by just to say Hello to Luther.

I was over 50, so Luther was over 50 as well, but there he was with his head under the hood of a ’57 Chevy, of all things. What had been his house adjoining the garage had been refurbished to accommodate two more bays, and he had two more hands.

From the looks of it he was quite successful, the more remarkable since the mine had closed a few years earlier. But since the town was so picturesque and the company houses so well-built, it became a popular retirement town for miners especially, coming all over eastern Kentucky and southwest Virginia. And he had a lock on getting their business.

I don’t know if he’d married or had kids, but I suspect so, simply because mountain women wouldn’t let a catch like that get away.

We didn’t talk for more than ten minutes, I guess. Nothing really to catch up on except how the town had fared since the mine closed.

But Luther Brock reminded me of another major rule of life, right alongside the “Ya ought not lie” lesson our classmate Mick Hensley had taught me in 5th grade; and that is success generally follows the person who bothers to find out “How Things Work” the quickest. Simple math. Luther’s understanding of the things that matter was better than half the corporate executives and 90% of the politicians and government administrative class that I’ve ever seen.

And this is why God, through a select few good men, placed the responsibility of knowing how things work in the hands of its citizenry and not its government.

Starting from that point, it’s much easier to connect the dots.