In the 1550s the Society of Jesus was formed by the soldier-monk, Ignatius Loyola, and became, for all intents and purposes, the missionary-military arm of the Catholic Church in its counter-reformation against the Reformation, with which the Church hoped to stem the tide of spreading Protestantism, especially inside the core of Catholicism in Europe; Italy, France and Spain. The Jesuits were a rare order, part military, part academic, part political, and part missionary, and they were willing to spread the Faith to the most inhospitable parts of the globe (i.e., the jungles of the New World, India and Far East). Taking vows of poverty like their Franciscan forbears, but with the highest levels of learning, they became a private arm of Church (foreign) policy for five hundred years.

Francis is their first pope.

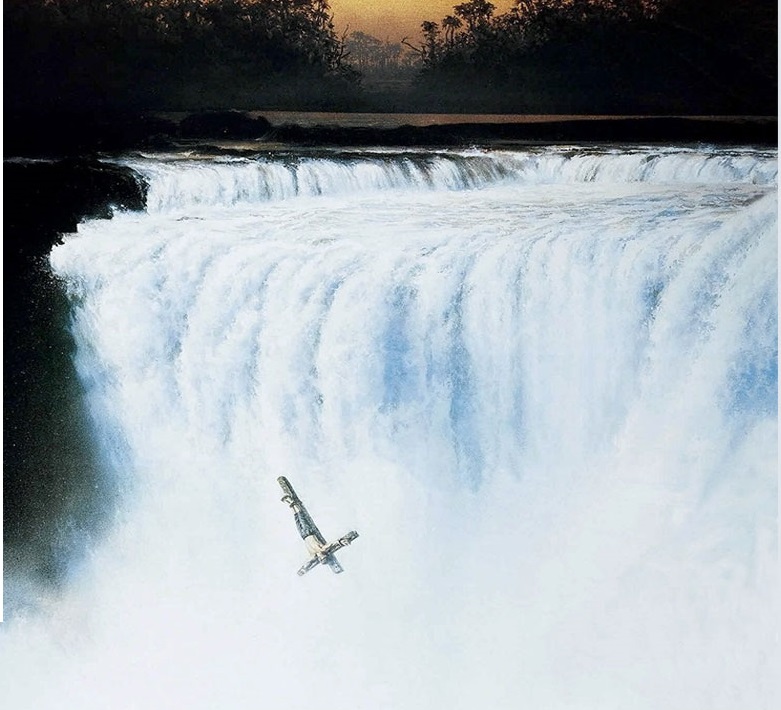

“The Mission”

There is a really very fine film from 1986 which I recommend. And with the Pope’s visit to the US, this might be the best time to see it, if even for a second time. It’s called “The Mission”, with great performances by Jeremy Irons and Robert de Niro, containing some of the most beautiful cinematography and most haunting music by Ennio Morricone, you’ve ever enjoyed.

It has a papal subplot that is relevant today, which is why I recommend it now. It’s based on a true story of a boundary dispute between Spain and Portugal in the Amazon region of Ecuador and Brazil, in the 1700s, and the fate of a church mission built there by a Jesuit priest who had risked all to go in among a tribe of head-hunters after other priests had failed. It seems that Spain had outlawed slavery among the Indians, while Portugal had not, and now that the headhunters had been pacified the Portuguese and their slave traders wanted the jungle boundary to be drawn so that the mission fell within Brazilian (Portuguese) territory so they could send in their slave hunters.

For modern political wonks, this was a simple moral issue versus a political-economic issue, with parallels found in modern history and politics almost every week.

The dramatic subplot in this film is between the Jesuit priest who built the Mission, (Irons) and a professional soldier/slave-trader (de Niro) who killed his brother in a jealous rage over a woman, so entered the priesthood and went to the Mission to study under for Irons as penance. One of the better film previews is here;.

Back to politics, the Holy See sent an emissary to adjudicate this boundary dispute, and he went up-country to see the Mission firsthand. There he witnessed the wonders of the change these priests had made, turning savages into beautiful and melodious children of God. (Very haunting.) The papal emissary then returned to Rome with his report where the Vatican, based on local political issues in Europe, determined that the boundary should be drawn in Portugal’s favor. The moral issues surrounding the Mission’s success, souls saved, etc. had nothing to do with the decision made in Rome. Sound familiar?

Both priests, Irons and de Niro, refuse to abandon the people at the Mission, but de Niro, the ex-soldier, said “not without a fight”, forsaking his oath of obedience. The conflict of choices between the two men, surrender or stand and fight, serve as the drama of the film, and is a tired theme, actually, only exquisitely depicted here. But the film, (it is Hollywood, after all), makes no comment at all at the cynical trade-offs back in Rome that brought these innocents to their fate in the first place.

But I am very interested in the history of the papacy’s use of trade-offs, which goes back centuries. In fact, the modern Church was built on one. This has caused the Roman Church all sorts of problems with spiritual consistency for over 1200 years, since from the earliest times it began wearing a second hat, that of political broker, largely to protect its new-found status among kings, and the security they could provide. After almost a thousand years of persecution, they could finally rest easy, when Pope Leo III laid a crown on the head of Charlemagne on Christmas Day, 800 AD, declaring him to be Holy Roman Emperor. A totally political deal, with a really sordid back-story having nothing to do with faith, the Church signed a power-sharing agreement with the Devil in Rome that day. No more, no less.

That was the Church’s first official trade-off.

Of course we recognize these as day-to-day political compromises today, and in almost every instance, virtue and goodness, right and wrong, the innocent, take a back seat at the expense of hard cold politics. self interest and power, providing what is agreed is the ugly side of Church history. It had been that way for centuries, only, since 1978, the moral trade-off practice had been suspended by two popes, John Paul and Benedict.

Now, with Francis, the question is, are religious trade-off’s back in fashion?

The good news of course, is that there has always been two Churches, the corporate and pastoral, and the parish church that still operates on the original preachings of Christ. This church I love, even as I can never be a member, as I dislike the corporate office so much. But I never get tired of watching the Eucharist, that celebration an unbroken handshake between generations for over 2000 years.

But about Mutter Kirche herself I am cynical. My favorite Catholic apologist, G K Chesterton, defended the Church of the Middle Age, arguing that such trade-offs allowed a flame to be kept lit in the darkness that could easily have been snuffed out by any number of kings had Rome chosen wrongly against the myriad of their royal demands. But at some point Rome realized it was safe from the Dark and, as mere humans are prone to do, could drink the Kool-Aid of shared royal power and wealth as well. After 800, secure from the barbarians they baptized, (but still barbarians to everyone else), they jointly ushered in a 600-year reign of slavery called feudalism, under whose auspices the Church was able to pour incredible opulence into Rome, while their parishioners in the boondocks suffered the worse for it.

This glitter of Rome insulted the young nobleman-turned-monk, Francis of Assisi, who in 1206, formed a new order to proclaim and renew the poverty of Christ. Successful in other areas, Rome and the Lateran Palace still seemed untouched buy the poverty of Christ three hundred years later when Martin Luther’s senses was assaulted by the same opulence while visiting there in 1510.

Enter Father Francis, the new Pope, the first Jesuit pope, and who has adopted the name of that first monk to take that vow of poverty in 1206.

George Will (yes, that George Will), an atheist, so I will only give you the shorter National Review version of his article, says that this pope seems to be pursuing economic policies that may well end up destroying his broader spiritual aspirations for the Church. Will argues that Francis is pursuing statist measures that only reduce the economic station of peoples (as has happened in his Argentina) and ultimately align with government institutions that, in the long run, may have no truck with Christians, and likely will suppress, reeducate or bury them.

At first glimpse Will seems to be right, for the Pope’s actions seem to be contradictory with his purposes. But maybe the pope is a naif (a possibility) or maybe has another scheme altogether, which Will has overlooked.

A naïve Francis may well not know the difference between a right-wing fascist thugocracy and a left-wing socialist regime. He certainly seems oblivious to the miracle of capitalism in a free America versus say the crony-capitalism (fascism) as found in authoritarian Latin American regimes. The Peron model in Argentine is but one. In many ways Francis comes off as a country pastor dressed in a king’s raiment. No one is ever sure what this Pope means when he speaks. His comments have to be re-stated and reinterpreted, only one is never sure who it is in the Vatican public relations office that is actually speaking for him when they speak for him. And the words may not even be his own. He has some very suspicious advisors (I think his climate science advisor is a Marxist). There are many competing factions there. And unlike John Paul, we are not even certain Francis is really in charge. There is a Peter Sellers aspect there that worries me.

But then consider Francis-the-grand-planner. Considering Francis’ history in a very stratified rich-and-poor country, and his vow of poverty, and his general belief in the wickedness of nations that have too much food, too big a house, too big a car, etc, and his belief that the more people have more they fall away from the Church (not necessarily God, mind you), there is also the possibility the Pope knows exactly what he is doing. You see, as already explained, the Church has a long history of power sharing with non-Communist pro-Christian authoritarians of the thug variety. And in South America it is still recent history.

Francis clearly is lecturing America for having markets that are too free, and unlike Jesus, who enjoined us to share with the less fortunate, as we largely have done for 300 years, believes it’s just fine for the state to stand in for us, in loco parentis, in carrying out this commission….at the standard going rate of 40% for the middle men. This arrangement pleases men like Obama.

We know Francis wants to see the Catholic Church grow in the United States. But knowing also the history of falling away from the Church by second-third-etc- generation Irish, Italian and east European Catholics, that they tend to be, not necessarily less Christian, but less Catholic (didn’t he ever see “Bells of St Mary’s”?) Francis likely feels that Hispanics are the best avenue for growing church membership here, especially since their free market slates are the blankest. New inventory, if you will. This is why he mistakenly calls illegals “pilgrims”. He’d rather see much of our wealth-producing capability restricted and one way to do that is tax the producers of wealth even more.

Such a policy is entirely territorial for the universal Church, for it does not recognize other sectss as legitimate. My city is filled with several Protestant -Latino congregations, 25-75 strong, (Baptist and Pentecostal mostly), I know some groups personally, all of whom came here as religious refugees of sorts, since they were persecuted by the bishop-led forces of governments in Peru, Bolivia, Salvador and Guatemala and other places. This has been the case for decades.

So, if this theory is true, what is Francis’ trade-off? Well, he must come to America and make nice with atheists who despise Christians. He’s done that. His public addresses have been largely secular and political and not pastoral. The Catholic world’s universal hatred for abortion, and the peculiar American practice of turning those dead fetuses (and sometime babies) into profit, has been largely overlooked during this visit. No finger wagging. No shame. Likewise some of our more gross pop culture sins; pornography and declining moral standards have gone unmentioned, or our government’s lack of action against the slaughter of Christians abroad by Muslim radicals.

This silence, combined with his gratuitous political grandstanding on climate change, portends those tax increases on industry and public consumption I just mentioned and tells me Francis comes bearing an offer of trade-offs: growing his Church, while keeping it housed and fed in the nexus of nanny state management in exchange for a papal license to take an even larger role in controlling American industry and business…and a wink and a nod about the treatment of the unborn…who, not unlike the fate of those Indians in Brazil, are still odd man out. This clearly favors the likes of Obama and Democrats more than it does the generational aspirations of Latin immigrant.

Still, after 35 years of hibernation, the era of religious trade-offs may be back among us.

But Francis’ timing couldn’t be worse. If you’ll note, American see, and despise, this same kind of trading off in our own politics, souring Republicans especially. And we want to burn it all down. He will gain no new friends here with such offers at this crucial time in our history. With the exception of the past two popes, the American catholic community has largely kept the Church in Rome at arms-length. A new detente may be setting in again.